Hippasus Gurgles: LOGICOMIX Review

Michael Carlisle examines the world “outside” sequential art to find… more sequential art.

I had the distinct pleasure, during a random walk down the aisles of BookExpo America last May, of finding a preview copy of Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth, which is due for release in the US on September 29, 2009.

First, I’ll say that I am overjoyed that this book exists, as it shows that mathematical content can be relayed, and relayed well, in the comics medium. I am also rather frustrated by the existence of this book, as I did not write it myself.

If I was to sadly be scooped by someone on the comic I wanted to write about mathematicians, logic, infinity, madness, world wars, and self-reference, then I would hope it would be by Apostolos Doxiadis (whose Uncle Petros and Goldbach’s Conjecture I’ve read only a portion of but am awaiting the rest) and Christos Papadimitriou (whose Combinatorial Optimization

text I used as an undergrad, and will use again when planning a course I’m teaching in the fall).

(Them, or maybe Neal Stephenson. But he’s already done a few things similar to this, in text, for cryptography, calculus

, and religion

.)

As is almost necessary for a work which claims to relay mathematical content, especially one which deals in modern logic, the book shifts in and out of the “primary” narrative in a self-referential fashion, as the authors and artists interrupt their own work to discuss amongst themselves the content they are currently developing. This effect subtly, yet expertly, relays the fact that the most interesting ideas in 20th-Century logical thought come from the intricacies of self-reference, of a “second-order” way of looking at things along with collections of things. How to do this? By having the book refer to itself, of course.

In the “primary” (first-order) narrative, the great logician Bertrand Russell regales an audience (some of whom have shown up to angrily recruit him into Britain’s WWII isolationist sentiment) about “the role of logic in human affairs”. He takes us through his life (modulo some artistic license), the development of modern set theory, logic, the crumbling and rebuilding of empires of thought, and the strange correlation between mathematics and madness.1

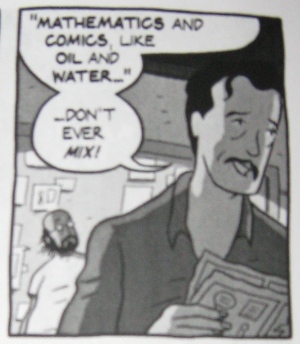

While I greatly appreciated the work, one panel in particular cut to my core: on p. 200 one of our authors laments,

While I was clearly2 engaged with the content and emotional trajectories of the primary narrative, I was struck by the effectiveness of these arguments between Apostolos and Christos (which I am guessing are often verbatim from “real life”, whatever that means) about how much math was ending up in the story, and how much was about the people and world of the story. Christos’ unspoken concern is that most mathematicians and computer scientists insist upon having as little “fluff” as possible outside of what is necessary to construct and understand an argument. Apostolos effectively counters with the fact that this is a story – literature, graphic or not – and not a textbook.

Another argument, about the authors’ different visions for the overall theme (“Logic and Madness” or “Reality vs. Maps”), feels more like “fluff” than the concern over mathematical content, but it still points to the (loosely-founded) worry from educators of technical ideas that something can be either educational or interesting, but not both. As I am trying to develop variants of this very idea I have some issues with the notion that we can either tell a story or do some math, but not both simultaneously. In the worst case you end up with something like Why Knot?, which equates “comics” with superheroes and speech bubbles, and in a far better case we get Logicomix. However, if our aim is actually developing some real, hard mathematical ideas, it’s not quite good enough. What do we need? A concerted effort to develop an entire semester course while simultaneously entertaining in a deep way? The content touched on in Logicomix takes many years of full-time study to develop a strong understanding of it. The core ideas, however (Russell’s Paradox, Hilbert’s Program, Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems…), are quick enough to state and are presented beautifully.

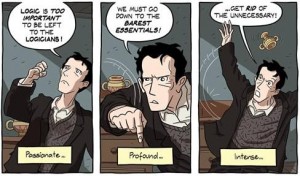

Ludwig Wittgenstein throws down.

Obviously the authors know this. They did not set out to write “Computer Science For Morons“3, as Apostolos says Christos wants, but a piece of literature about people (the logicians and the creators themselves) and the ideas that drive them, and as that it is superb.

Overall, I was quite engaged and intrigued by the historical notes throughout the book (although, as the authors state in the epilogue, a bit of license is taken for narrative efficiency). The inclusion of a mini-encyclopedia (replicated on the book’s website) is indispensable for anyone that wishes to learn more about the real people and their work. Finally, a brief bibliography points the curious reader to more.

As an ABD mathematics student and teacher, I’m squarely on Christos’ side, but have been more and more accepting Apostolos’ argument. If it took Russell and Whitehead ten years to finish the Principia Mathematica and the only person Russell believed read it all the way through was Gödel, then I completely understand feeling one must add as much expository material as necessary to get someone to actually care to partake in hard work. Why not put faces, attitudes, and war in the mix? Otherwise it’s all just so much formalism. Sorry, Bourbaki, you’ll have to take one for the team here. We need more than just symbols to get us into caring about math.

As my logic goes, perhaps comix will do.

—

[1] Story of my life………

[2] One of those dangerous math terms; some others are “obvious”, “trivial”, and “easy to show”.

[3] … of which there are already quite a few, thank you.

—

Michael Carlisle is a mathematics Ph.D. candidate at the City University of New York, where he earned a certificate in Interactive Technology and Pedagogy. When not teaching or researching probability or rambling about dystopian films and surrealist animation, he volunteers with the Sequential Art Collective and New York Center for Independent Publishing.

Interesting ideas converging to most of the concepts discussed with my nephew(Michael) who hated learning “math” and has rediscovered the magic and power of the discipline through Comics ,Animation Technology,

and Art ( attempting to master “Maya”)… He’s teaching teachers while

reappraising his views on Math!!